Kyiv Patriots head coach Alfie Williams speaks to Sky Sports about his players fighting on the front line in Ukraine, a year on since Russia launched their full-scale invasion; Williams was recently invited to attend the Super Bowl as he tries to raise the profile of Ukrainian football

A year on since the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Alfie Williams still speaks with his players on the frontline unknowing as to when they might speak next, if at all. Often they cannot tell him where they are, nor where they are heading for security reasons, though there tends to be one thing they wish to talk about most when coach gets in touch – football.

“The guys are fighting but they still had their fantasy leagues during the season, they were still watching NFL clips on YouTube whenever they can get access to the internet,” Williams, the head coach of the Kyiv Patriots, told Sky Sports.

While the outside world sees the military overall from a sympathetic but generalised vantage point, the former Ukrainian National Team head coach sees his wide receiver, his offensive tackle, his edge rusher and his safety as those with whom he has worked and befriended willingly defend their home.

Williams makes note of one Patriots player they call ‘Ded’ as in Dedushka “because he’s basically Grandpa” being in his 40s and still playing; elsewhere on the team are lawyers, doctors, businessmen, fitness instructors, men in marketing, “kids just trying to figure it all out in school”. His players, his friends; normal men with normal jobs, doing the unnormal.

“They’re wonderfully crazy guys with a lot of different personalities,” he explains. “A lot of guys with big hearts. You also get the funny things you have with any football team, like this guy might be a little bit of a diva because he’s a receiver.

“It’s always fun, there’s a lot of pride, determination, I wouldn’t say stubbornness as such but doggedness, they have a lot of that will to move forward. It makes it very easy to coach them, they don’t really care about the physicality, they’re not afraid of anything, they’re fearless. I’ve been saying as I’ve been going through this that Ukrainians fight the same way they play football: tenacious, a lot of heart, they won’t back down and I think that’s indicative of how things are with the country as a whole.

“I could go on for hours and hours one by one about these players. Some of my favourite people are there.”

Williams, a Washington DC native, had no intention of getting into coaching when he arrived in Ukraine eight years ago, since which he has found both a wife and a football family. Ukraine is home to him by now, making for the toughest of 12 months.

“What happened was you fall in love with the guys and then you want them to succeed,” he adds. “Now that feeling has shifted to wanting them to succeed in football when things get back to normal one day, hopefully soon, but now you want to succeed on a different field of play so to speak.”

Rewind to the week of 21 February 2022 and Williams was still of the belief nothing would come of familiar Russian threats, nonetheless he and his wife headed to Lyiv as they waited for “everything to blow over”. Russian troops would invade on February 24, after which a nationwide scramble to move loved ones clear of conflict resulted in it taking three days for Williams and his family to get out of the country. He has since been situated in Berlin, and started his “from scratch” in many ways.

“While you’re doing this you’re hearing the news back home, talking to family back home, it’s been really up and down. I have my brother-in-law, father-in-law still there in Ukraine, mother-in-law goes back and forth to see them,” he says.

“Then we get the Ukrainian League of American Football element of it where we have guys on the front line, we’ve lost guys fighting against Russia and that always brings it back home. Whenever there’s a period when things kind of seem calm, you hear news players I know or have coached have died fighting on the front line, and we still have people there now. It’s been one of the strangest years, it’s been a weird up-and-down rollercoaster ride.”

He recalls an immediate, obligatory ‘what can we do?’ reaction from his Kyiv Patriots players, many of whom Williams says saved superiors the trouble of drafting them by entering the military unprompted.

“One of the first people from the ULAF that died during the war was a Kyiv Patriots founder who was in the military and he went when Crimea was taken so we do have that background,” he said. Yurii (Yurii Hundych) who founded the team and is now the president of the league, he said ‘I’m joining the military’, he didn’t hesitate, he enlisted and knew it was important.

“You get this weird sense of pride because you’re really proud of the guys and as a friend and coach it’s what you’d hope they would do, but at the same time, you’re horrified because every time you chat you don’t know what’s happening or if it’s the last time. You get these long gaps in communication and you’re stuck in the middle wondering ‘is everybody ok, what’s going on?’. I want to know, but I don’t want to bother them too much but you’re also so proud of them. There is this really strange feeling, you just hope everybody is alright.

“The ULAF community is pretty strong and everybody wants to do their part so you have guys from the Patriots and so many teams coming together to do what they can to continue to give.”

Their involvement entails ‘anything and everything’, many taking up arms and fighting on the frontline while others work to collect and distribute humanitarian aid.

“That’s something on paper that seems like there’s a lot of but the process of getting humanitarian aid is not as easy or simple as people would believe,” he says. “Also you have those men and women who volunteer in the field but are not official military so they have to get their own equipment, that’s when you’ll see people say ‘we need donations to help buy this jeep so they can patrol or helmets, shoes’. Me and my wife work with various people sending tourniquets and boots to people so they can have what they need.”

In the moments Williams does get in touch with players he makes a point of looking to the future, sparing just a few words to discuss a war they wish to leave in the past. He is longing for the day when the only thing he need worry about is how many people turn up to football practice.

“The international development of it, the funding; this war will end, but our big thing is what happens immediately after because there’s going to be a rebuild,” he said. “Maybe it’s next year the rebuild starts but we want to start the ground work for that and that’s why I previously spoke about the humanitarian part of things because again when the war is over they’ll no longer need these guns and bullets and armour, they’ll want to get back to normal.”

For Williams the self-assumed job is laying the table of sorts for when his roster returns, ensuring Ukrainian football is in a position to survive and prosper upon victory.

“There are fields that have been destroyed and football stadiums, what do we do with that? What about the mental health, the rehabilitation of these guys? That’s been the main focus,” he says. “It’s very difficult because you want to say ‘stay safe’ but I know that’s not the case. Nowadays I just say ‘I hope you have a calm day’ at least, and tell them to just keep giving them hell and hopefully we’ll get back to it.

“They’re very limited with what they can discuss with me from time to time but at least we can focus on the future, everything from getting the fields ready to getting the equipment, trying to set up things like coaching clinics.

“We’ve been very fortunate the NFL has paid attention so now we see a possibility to do even more things internationally, the timing works with the NFL because they’re growing more internationally so there are a lot of things we can look forward to once we get through this bit and end the war and everybody comes home safe.”

The effort to raise the profile of the ULAF has seen Williams connect with former New York Governor Georgia Pataki, whose trip across to Ukraine in December inspired the idea of his Footballs for Freedom initiative helping to donate supplies to players.

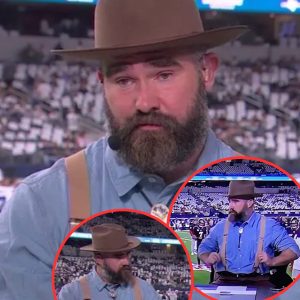

It was subsequently agreed that Williams and league president Yurii Hundych would attend Super Bowl week in Phoenix, Arizona as guests of the NFL, reminding of the need for continued support while raising awareness surrounding the Ukrainian league.

“Three people from Ukraine came with us, two of them soldiers, all three are men, so between 18 and 60 you can’t leave and you have the military aspect,” he recalled. “We went about this process of first letting the government know so they could leave, then the military letting them have a two-week kind of sabbatical as long as they came back. On top of that, we had to get the VISAs, which was also tricky because the embassy in Kyiv wasn’t working so everything just worked out.”

Eventually it all came together, a week of Radio Row interviews and Good Morning Football appearances culminating in a dream Super Bowl experience.

But with the glitz and glam of the NFL’s showpiece week came a stark reminder of circumstances back home, Williams hopeful his trip Stateside can prove a catalyst for further expansion.

“We will continue to speak with the NFL, there are a lot of things they want to help with moving forward with just promoting the ULAF internationally and just seeing what we can do with this and keep the momentum going,” said Williams.

Williams will continue to talk and to spread the word. He will continue to chat to his players about the time they can run routes and sack quarterbacks again, he will continue to coach from afar.

“I know they can deal with it, I know they have the mental capability, the heart.”